Precedent Setting Cases

The building blocks of righting wrongs in the U.S. can be found in the cases that surround you. Precedent—using past court decisions to inform present and future cases—is a fundamental principle of the U.S. legal system, and tort law is no exception. The landmark cases presented here reflect the constantly evolving nature of tort law and how it has adapted to meet the ever-expanding definition of individual and corporate responsibility.

1860 Brown v. Kendall

George Kendall tried to stop two dogs from fighting by striking at them with a four-foot stick. When he raised the stick, he accidentally struck George Brown in the eye. The court determined that Mr. Kendall could not be held liable unless he acted carelessly or with the intent to do harm. This decision was one of the first and most important to recognize fault as the basis for liability in tort in the United States.

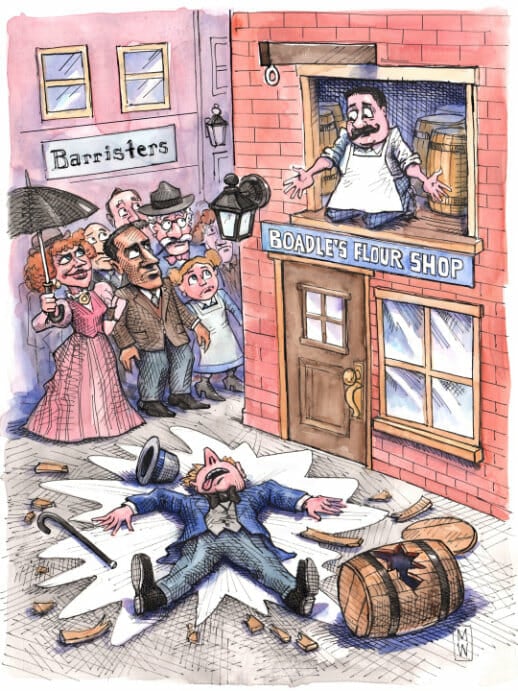

1863 Byrne v. Boadle

A barrel rolled out of a shop window and struck a passerby. The evidence at trial did not show why the barrel came loose. The court determined that the person in control of the barrel could be found negligent anyway because this was the type of accident that would not have happened without some kind of carelessness. This case established that, under certain conditions, carelessness can be inferred from circumstances.

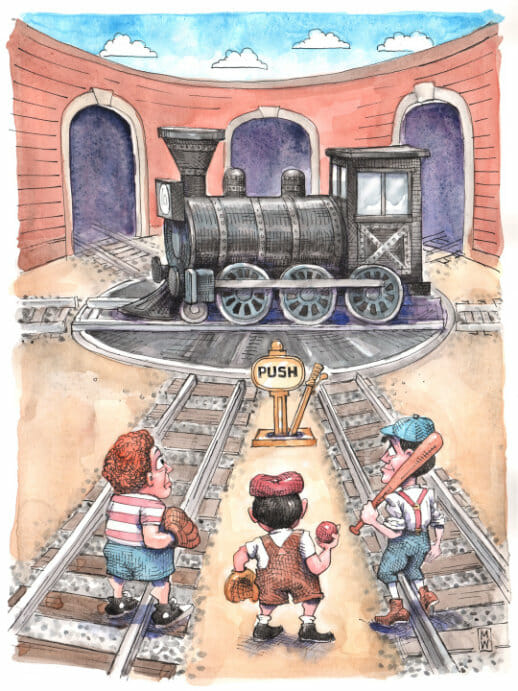

1873 Sioux City & Pacific Railroad Co. v. Stout

A six-year-old boy lost his leg while playing on a piece of machinery on railroad property. The case established the attractive nuisance doctrine, which means that landowners might be responsible for injuries to children if (1) they know or have reason to know the children are trespassing, (2) they fail to use reasonable care to protect the children from dangerous objects on their land, and (3) those objects are likely to attract children and then injure them.

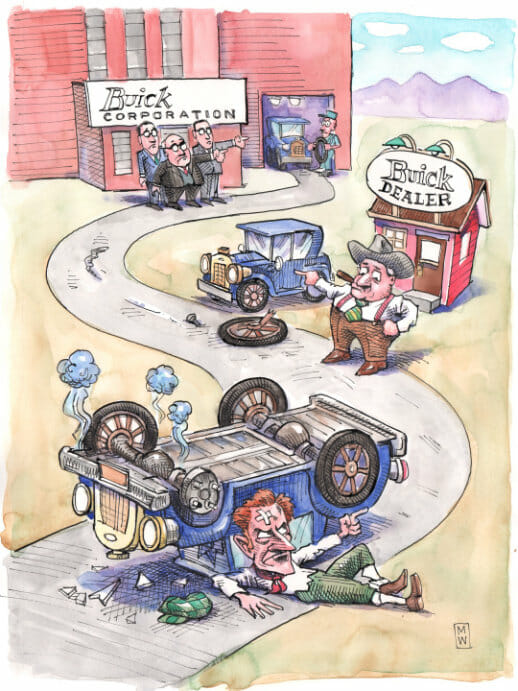

1916 MacPherson v. Buick

A jury found that a defective wheel on a new Buick automobile collapsed and caused the vehicle to overturn, injuring the driver, Donald MacPherson. The highest court in New York held that the driver could recover from the manufacturer due to negligence, even though he bought the car from a dealer and had no contractual relationship with the manufacturer. The basis for liability was not the contract, but rather the manufacturer's knowledge that vehicles with defective wheels could cause accidents.

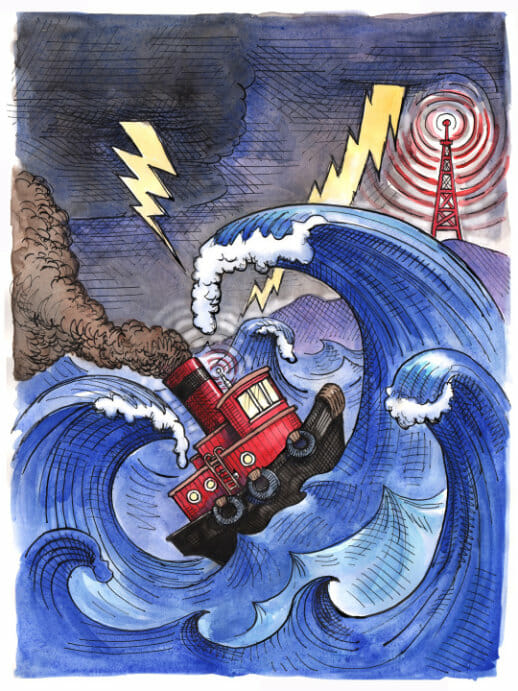

1932 T.J. Hooper et al. v. Northern Barge Corp. et al.

Barges towed by tugboats sank during a storm. The tugboats did not have working radio receivers capable of receiving a storm warning. In a case brought by the barge owners against the tugboat owners, the court held that a defendant might be liable even though he/she complied with industry custom, if a reasonable person would have taken the additional precautions. This rule has also been applied in ordinary negligence cases.

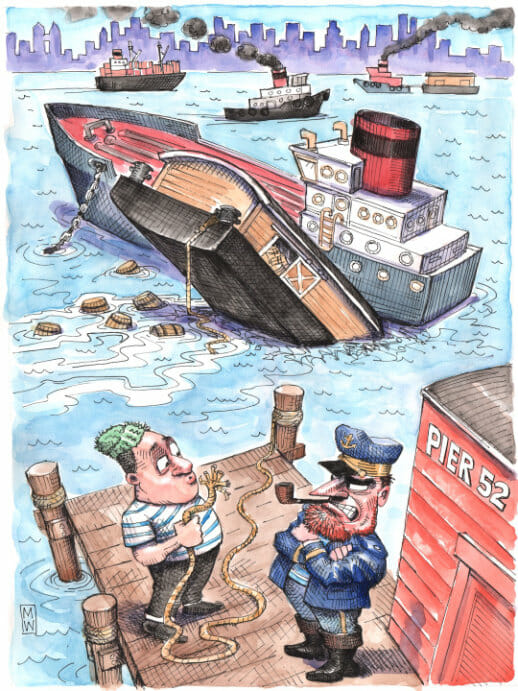

1947 U.S. v. Carroll Towing Co.

The Anna C, a barge, broke loose from its moorings and sank. The claim was that the barge sank because no employees were on board to work the pumps. The ensuing tort case involving the Anna C, Carroll, and the operator of the pier, produced a classic test for determining carelessness/negligence. The test required the court to decide whether adequate measures were taken by the barge owner to prevent a risk of harm to the barge: If the foreseeable cost of having an employee on board the Anna C was less than the cost of the foreseeable damage that might result to the barge without an employee on board, then the barge owner would be considered legally at fault.

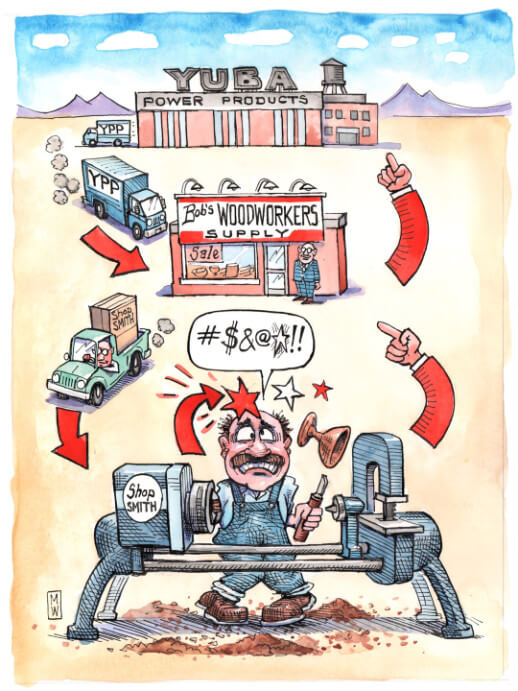

1963 Greenman v. Yuba Power Products

William Greenman was using a combination saw, drill, and lathe when a piece of wood flew out of the machine and hit him in the forehead. This case recognized the doctrine of strict tort liability, which means that the manufacturer of a flawed product is responsible for injuries caused by the product even if the manufacturer was not negligent in manufacturing it.