Grimshaw v. Ford Motor Company, 1981

The Pinto, a subcompact car made by Ford Motor Company, became infamous in the 1970s for bursting into flames if its gas tank was ruptured in a collision. The lawsuits brought by injured people and their survivors uncovered how the company rushed the Pinto through production and onto the market.

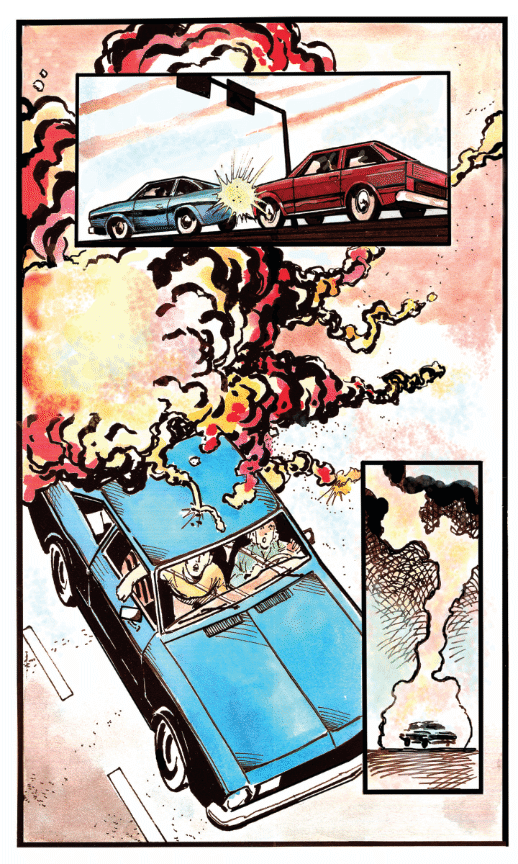

In 1972, a Ford Pinto driven by Lilly Gray stalled as she entered a merge lane on a California freeway. Her Pinto was rear-ended by another car traveling about thirty miles per hour. The Pinto's gas tank ruptured, releasing gasoline vapors that quickly spread to the passenger compartment. A spark ignited the mixture, and the Pinto exploded in a ball of fire.

Gray died a few hours later. Her passenger, thirteen-year-old Richard Grimshaw, suffered disfiguring burns and had to endure dozens of operations. He underwent surgery to graft a new ear and nose using skin from the few unscarred portions of his body.

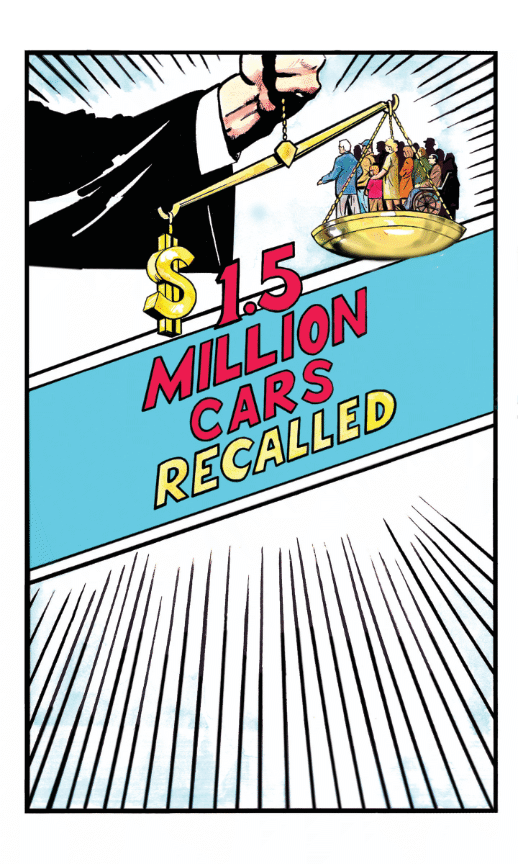

Grimshaw and Gray’s family filed a tort action against Ford, and the jury awarded not only $2.516 million to the Grimshaws and $559,680 to the Grays in damages for their injuries, but also $125 million to punish Ford for its conduct. Ford appealed the judgment, and the court reduced the award of punitive damages to $3.5 million. However, the court denied Ford's request to have the punitive damages award thrown out entirely, finding that Ford had knowingly endangered the lives of thousands of Pinto owners.

view the exhibit

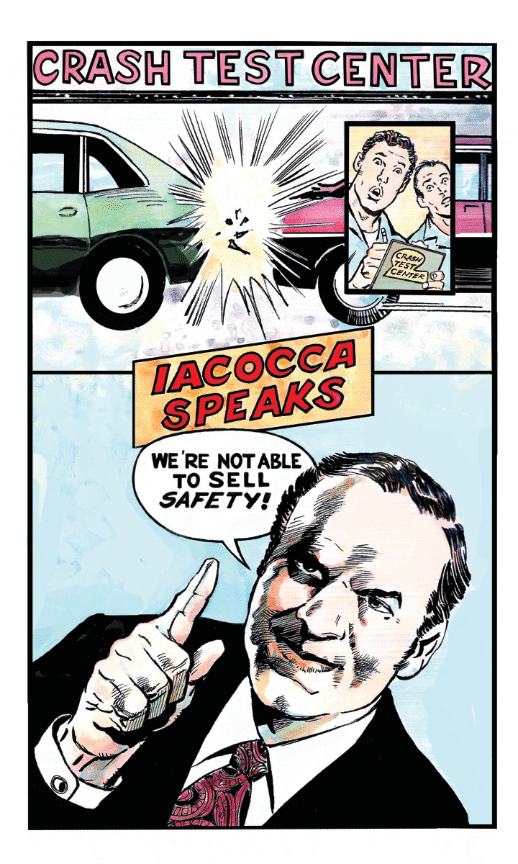

Internal company documents showed that Ford secretly crash-tested the Pinto more than forty times before it went on the market and that the Pinto's fuel tank ruptured in every test performed at speeds over twenty-five miles per hour. This rupture created a risk of fire.

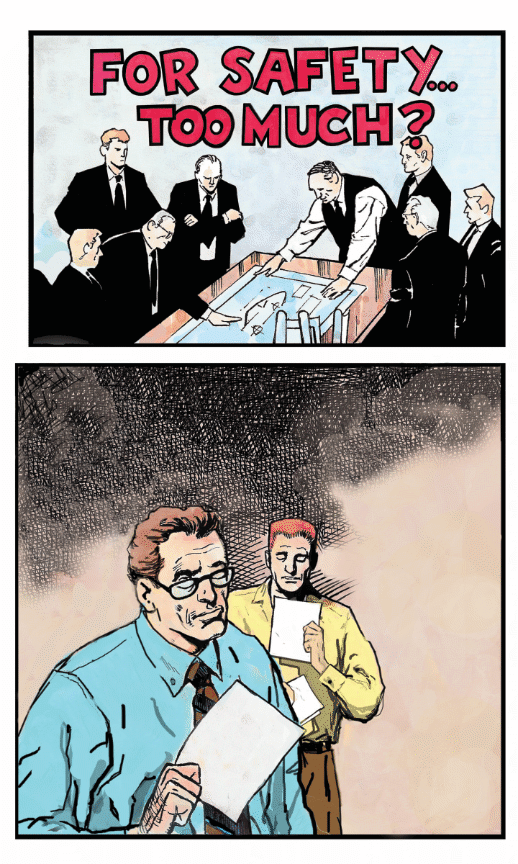

Ford engineers considered numerous solutions to the fuel tank problem, including lining the fuel tank with a nylon bladder at a cost of $5.25 to $8.00 per vehicle, adding structural protection in the rear of the car at a cost of $4.20 per vehicle, and placing a plastic baffle between the fuel tank and the differential housing at a cost of $1.00 per vehicle. None of these protective devices was used.

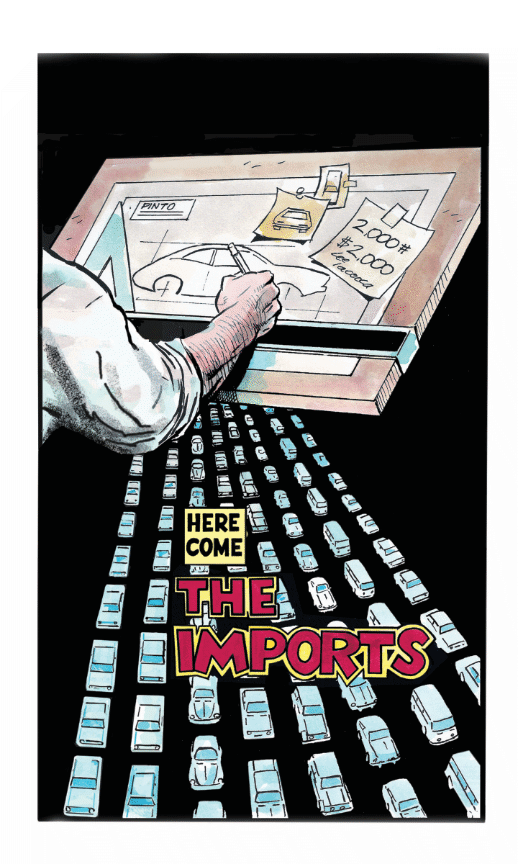

Adding to the pressure to ignore these safety costs was Lee Iacocca's stated goal that the Pinto was not to weigh an ounce over 2,000 pounds and not to cost a cent over $2,000. So, even when a crash test showed that a one-pound, one-dollar piece of plastic prevented the gas tank from being punctured, the alternative was thrown out as extra cost and extra weight.

When Ford was developing the Pinto, the company needed a low-priced car in a hurry to compete with Volkswagen and Japanese imports. Iacocca, a rising star at Ford due to his success with the Mustang, argued that Volkswagen and the Japanese were going to capture the entire American subcompact market unless Ford produced an alternative to the VW Beetle. As Executive Vice President and later as President of Ford, Iacocca was the driving force behind the program to produce the Pinto.

The Pinto was rushed through production in just twenty-five months so it could be included in Ford’s 1971 line; the normal time span for a new car model was about forty-three months. During the accelerated production schedule, Ford became aware of these serious risks associated with the Pinto’s fuel tank but proceeded with its manufacturing schedule anyway. Company officials also decided to proceed even though Ford owned the patent on a much safer gas tank.

Did anyone go to Iacocca and tell him the gas tank was unsafe? "Hell no," said an engineer who worked on the Pinto. "That person would have been fired. Safety wasn't a popular subject around Ford in those days. With Lee it was taboo." Iacocca used to say, "Safety doesn't sell."

Why did the company delay so long in making these minimal and inexpensive improvements? Simply, Ford's internal "cost-benefit analysis," which places a dollar value on human life, said it wasn't profitable to make the changes sooner. Ford's cost-benefit analysis showed it was cheaper to endure lawsuits and settlements than to remedy the Pinto design.

Ford knew about the risk, yet it paid millions to settle damages suits out of court and spent millions more lobbying against safety standards. Pinto was a best-selling subcompact. By 1977, new Pinto models incorporated a few minor alterations necessary to meet federal standards that Ford had managed to hold off for six years.

The Grimshaw case was just one of more than one hundred lawsuits that were filed because of design flaws in the Pinto that resulted in fuel tank fires. Estimates by Mother Jones attribute between 500 and 900 burn deaths to Pinto crashes. These people would not have been killed or even seriously injured if the car had not burst into flames.

The Grimshaw case sent a message to automakers that if they chose to ignore safety considerations, it would be at their own financial peril. This case helped push the automobile industry away from "safety doesn't sell" and toward emphasizing new safety features in their marketing.

In 1978, following a damning investigation by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Ford recalled all 1.5 million of its 1971–76 Pintos, as well as 30,000 Mercury Bobcats, for fuel system modification. Later that year, General Motors recalled 320,000 of its 1976 and 1977 Chevettes for similar fuel tank modifications. Burning Pintos had become a public embarrassment to Ford. Its radio spots had included the line: "Pinto leaves you with that warm feeling." Ford’s advertising agency, J. Walter Thompson, dropped that line.